Introduction to Monthly Cycle Program 5784

Fall is just starting. The stems of the pepper plants are showing their age and the corn stalks are slowly losing their green color in favor of brown. The first trees are losing their leaves just as some change color. The cicadas are still noisy when it warms up, but the birds are quieter, their mating rituals ancient history from the spring, the young raised for the year. The stags are in rut, and I see them occasionally after missing them all year, just as I see their presence on a few more trees in the woods.

The world is turning again, as it has for millions of years, an unending cycle in which we have been formed, like water to a fish. There’s a rightness to this rhythm, even as I miss the heat of summer and don’t look forward to the cold of winter. In my prayers, I praise the divine for the cycle of birth and death without which the beautiful world would not exist. I remind myself that there is no death without life, an obvious concept, and there is no life without death, a more difficult concept. I pray for as deep an understanding as possible that I, like all beings, are part of this cycle of life and death, whether I embrace it or not.

We live in a society that denies the cycles of our lives and of the world. Our society teaches us that “age is just a number” and offers us magic potions to pretend that we will live forever as adolescents, as if that were a desirable thing. This book is grounded in a different vision that embraces the cycles of our lives and of the world. No eternal summer, no eternal youth, but an engagement with the cycle of birth and death.

This program is an invitation to spiritual development in the context of our being embodied humans held by the more than human world, as mediated through our Jewish tradition. The more than human world is a term I take from David Abram’s wonderful book, The Spell of the Sensuous. This refers to what is often called nature, except that we should understand ourselves as part of this world, not opposed to it or divorced from it in any way other than in our misguided thoughts.

This program is an invitation to spiritual development that seeks alignment with the divine and the more than human world. This is my goal as a committed religious practitioner. I do not believe that you can be aligned with the divine apart from being aligned with the more than human world. I deliberately leave aside the theological question of how to understand the relationship of the divine and the more than human world.

This spiritual development is mediated through Jewish tradition because I am a Jew. I believe that the questions I ask will be of value to you even if you are not Jewish, as based on my experience of teaching parshat hashavua, the portion of the week that we read from the Five books of Moses, to non Jews.

I believe that Halacha, Jewish law, should be understood as precisely an attempt to align the human and the divine through humans doing what God wants them to do as mediated by the Rabbis and by law. If Halacha works for you, great. This book works with the idea that the divine and human worlds can only be aligned through the mediation of the sensual natural world. This is something that, in my experience, has been largely missing in Jewish literature, though there is some presence of it in certain schools of Kabbalah. It is certainly something that I would have avidly absorbed had it been available when I was younger. The reader should judge for him/herself how well the program succeeds. Also, other earth based interpretations are certainly possible, and I would indeed expect that someone deeply connected to a Mediterranean ecosystem will feel the seasons differently than I do.

You might ask who I am to write this book. I’m not a Rabbi or any kind of psychologist. While I earned Masters’ Degrees in both religious studies focusing on interpretation of archaic religion and a Masters in Social Work, those were a long time ago. I’m also no great guru who has spent thousands of hours meditating in a cave and emerging with such powers that I had to go back in until I learned to control them, such as Rabbi Shimeon Bar Yochai and his son (Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 33B-34A). I earn my living running a business I co-own, and I have been an inconsistent religious practitioner for a long time. I have a particularly strong connection to the land in the eastern US, particularly to cows and to pastures. I have a rather deep connection to Judaism as a people and to earth based religion. That’s what qualifies me to write this book, if I am qualified at all. Mostly I know that my path to the divine is mediated through land and through my belonging to a particular tribe. That’s what I am seeking to capture and invite you to share in this program.

HOW THE PROGRAM WORKS

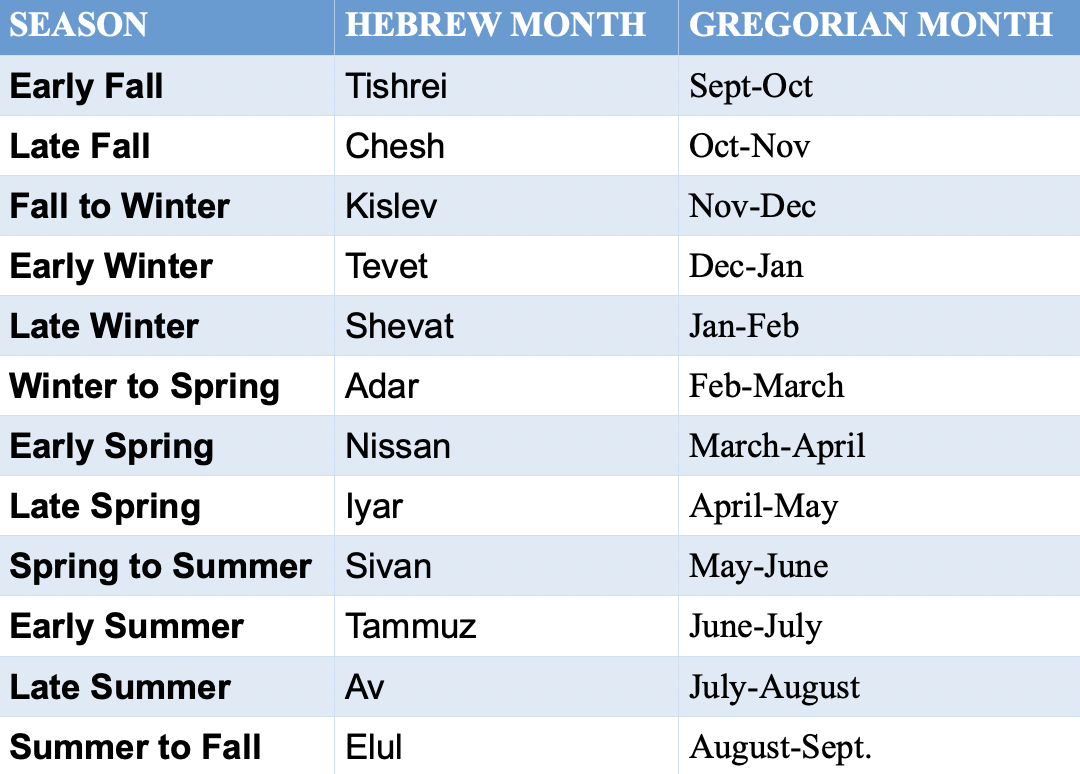

I have divided the year into 12 parts. Here’s a chart:

This is a linear chart which has the merit of being easier to read. But really it is a cycle. Here’s a representation.

The Hebrew calendar is a combination of a lunar and solar calendar. Months are based on lunar cycles, starting with the new moon, waxing to the full moon in the middle of the month and then waning for the back half of the month, until the next new moon marks the beginning of the next month. The lunar calendar doesn’t perfectly align with the solar calendar that we typically use,(the “Gregorian” calendar above) and the Hebrew calendar has an ingenious adjustment where we add a second month of Adar every 7 years out of 19 in order to keep the lunar calendar aligned with the solar calendar. The result is that Pesach (Passover), for instance, always occurs in the Spring. If we were following a strictly lunar calendar, as does the Muslim calendar, the holidays would rotate. For instance, Ramadan can occur at any point in the year—winter, spring, summer or fall.

The advantage of this calendar is that the months are actually connected to the natural phenomenon of the lunar cycle as well as the seasons of the year. The solar calendar does not have this lunar correlation. In the solar calendar, the new moon and full moon can occur at any point in the month—for instance I wrote the first draft of this paragraph on the 11th of Av 5777 and the full moon will happen in the next few days—the 5th or 6th of August, 2017. The new moon for the month of Av actually happened in July. That’s one small reason why we modern humans have lost contact with lunar cycles—they are not reflected in our calendar.

The structure of each chapter is purposefully repetitive.

The first part of each chapter is a (hopefully) lyrical and sensual evocation of what is happening in my backyard and garden in a Continental Climate. I live in the mid-Atlantic, and the timing would be a bit different if I lived in Vermont or in the flat areas of North Carolina, but Continental climates have a certain 4 season rhythm that I attempt to capture. I then raise questions for our spiritual development based on what is happening in the more than human world. For instance, for the month of Tishrei where we are doing a lot of harvesting, I ask what needs to be harvested in your life? I usually ask three or four questions.

There are a broad range of possible ways to engage with the questions. I journal, but I would encourage exploring other ways to engage such as doing artwork or any sort, self-created ritual, dancing answers, voice dialogue with what is being harvested etc.

I will sometimes take a pass at what is happening in Mediterranean Climates. I have lived in Israel (but not for a long time) and 2 season climates in the Pacific Northwest. I don’t have a good feel for these climates. These climates inform our inherited holiday calendar, so I will discuss this as pertinent. This experience of wet winters and dry summers provided the context of our ancestors experience of the more than human world. We have to take this into account.

The second part of each chapter discusses the Jewish holidays that occur during the month, if any (Cheshvan, the month after Tishrei with Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur and Sukkot has no holidays). There are a lot of good books about Jewish holidays, and I’ve no desire or expertise to add to the general discussion, though I will reference some of it. My focus is going to be on their agricultural component and their relationship with what is happening in the ecosystem. I will then raise questions for our spiritual development that relate to the holidays. As an example, for Sukkot which is about pleading for life giving rains based on being in alignment with the divine, I’m going to ask where you are in alignment with the divine and more than human world and where are you not. I’m going to ask what kind of blessings you want to rain down on you in the next year. For Tu B’shvat, the new year of the trees, I’m going to ask what is ready to bloom like the Almond tree in Israel (this is what typically blooms then) or witch hazel in Continental climates.

The third part of each chapter is an overview of what we are reading in the weekly Torah portion from the five books of Moses, more or less. Readers should be aware that depending upon timing of the holidays in terms of Shabbat and whether it is a leap year or not, we don’t read the same thing if you look at the second shabbat of, say Elul, each year. I will again ask a few questions drawn from the different parshiot (portions) that address our spiritual development and the more than human world. I’ve written and taught much more extensively on each parsha. Interested readers can go to https://earthbasedjudaism.org/parsha-commentary and find much fuller discussions.

My reading of the holidays and the Biblical text is highly influenced by my perspective on them as myths full of symbols. I mean something very specific by these terms that are used in some many ways that they are unusually ambiguous.

“Myth” is a term that is used in many different ways. I have been a student of myth on and off, including academic study, since the 1980’s. A recent good introduction is by Robert Segal Myth, A Very Short Introduction. I’m going to propose a very specific definition of myth which is largely drawn from the work of the great Historian of Religion, Mircea Eliade, augmented with Paul Ricoeur’s theory of symbols. Eliade’s theory can be found in his books The Sacred and the Profane and Patterns in Comparative Religion. Ricoeur’s can be found in his Symbolism of Evil and Interpretation Theory.

One further note. I’m not claiming that this definition of myth is the “truth” or the only way to look at myth. I’m making a philosophically Pragmatic (think Richard Rorty with whom I studied, following John Dewey) argument; I think this way of looking at myth is useful if you have spiritual goals such as being aligned with the divine or becoming a spiritual adult. So I am explicitly not embracing any of the definitions of myth that focus on myth as being proto science or having a role in a certain kind of technology (Tylor, Frazer, Malinowksi). I’m not interested in the way myth functions to further societal goals (Durkheim, Levi-Strauss, Turner). I’m not saying that myths do or do not work that way; I’m just saying that if we are interested in being aligned with the divine, those views of myth are not helpful.

Here’s the definition.

“Myths are enduringly relevant stories of revered ancestors, Gods or beginning times that incorporate symbols.”

Myths are stories because the structure of stories can capture the experience of the divine in a way that other discursive forms cannot. The experience of the divine does not adhere to a linear structure and often has fantastical elements—and so do stories. Stories open up worlds to us.

Revered ancestors include our human ancestors such as Abraham, Moses, Miriam, David, Esther, Hasidic Rebbes etc. Myths aren’t limited to Gods or to creation. Thus I would reject the argument that myths only apply to polytheistic religions. Our tradition, as I will show, is replete with myths.

Myths include symbols. “Symbols” here has a technical meaning, taken from the writings of philosopher Paul Ricoeur. Symbols, by Ricoeur’s definition, are things rooted in the natural world that also point beyond themselves to the sacred. Prime examples are the moon, rocks, circles, wells, rain, clouds, cycles of the seasons. They can’t be fully explained by language. They have a quality of mysteriousness, of opaqueness, of not being fully captured by language. The presence of symbols in myth also serves to lure us into different worlds.

The upshot is that myths are a deep well that can lead us into the divine. They, by my definition, cannot simply be explained—or else they are not myths. Eliade says somewhere “myth is truer than fact”. I take it that he means that myth goes deeper than mere fact because it speaks to our relationship with the divine in ways that science and the language of facts simply does not. Myth will play a key role in our earth based exploration of our relationship with the divine.

Of course, if you can create your own deep questions stirred up by what I have shared and/or your own knowledge/experience of the more than human world or of our tradition—that’s wonderful. That truly shows that you are engaging with the material.

The themes and questions, to reiterate, can be explored through journaling, dream work, prayer, any kind of expressive art or a wide variety of other practices. If you have a community where you can explore them with other like minded people, then know that you are blessed and please pursue them this way. If you are doing it by yourself, that works as well.

WHERE TO BEGIN?

We’re taught early on in life that every story has a beginning, a middle and an end. Our lives, even as they contain echoes of countless lives, human and other than human, have what we experience as a beginning a middle, and an end, at least as others experience it. Our tradition has as its main time schema a beginning with the creation of the world in Genesis, a middle known as human history, and an end known as the Messianic era. At least that’s one way to tell the story. But I want to tell the story differently.

Jewish tradition recognizes four new years. (Mishnah Rosh Hashanah Chapter 1) There’s the new year known as the new year, Rosh Hashanah. Only it occurs in the seventh month of the year. There’s the new year that starts in the new moon of Nissan, (Leviticus 23) only the holiday that occurs then is actually at the full moon, not the new moon. (Hebrew months start at the new moon). There’s the new year of the trees during what is winter here but is at the very start of spring for a Mediterranean climate when the almond trees flower. It’s also at the full moon and we aren’t trees, though we need a lot more trees to help mitigate climate change and they might wind up saving our sorry behinds. The new year of trees has become something we celebrate (Tu B’shvat) but it started out as a tax date for trees, a kind of April 15 for the trees. Anyone want to make April 15th a holiday? Then there’s the obscure one I always have to look up, the first of Elul which is the animal equivalent of Tu B’shvat, another tax day and is not widely celebrated, though some are seeking to reclaim it.

Then there’s the opening line of Genesis that most of us learned as “In the beginning God created the Heaven and the Earth.” Only when our ancestors decided to add the vowels to the written consonants in the Masoretic text (seventh century CE) they didn’t add the vowel that indicates the definite article “the”. So there’s been a long argument about how to translate the opening of Genesis, and certainly a less linear reading is plausible (for a longer, more technical discussion, read this (http://kehillatisrael.net/docs/dt/dt_bereshit.html)

So where to begin? It isn’t obvious. It would seem as if our tradition contains both a linear concept of time and a cyclical one. This correlates with our own experience; the year is cyclical, but our individual lives have a beginning, middle and end, even if we are usually not given to know when the end is, and it is difficult to know where we are in our own story. The more than human world equally has both linear and cyclical aspects. Beings are born, live and die, and they live in a cyclical context if they live long enough where they see multiple sunsets and sunrises, multiple seasons. So where to begin? Begin where you are. Maybe that is based on the time of year you first pick this up. Maybe that is based on the questions that seem to be burning for you. Know that this is a cycle, so there is always an opportunity to revisit what you might have missed.

I’m going to start in Tishrei, but there is a part of me that always feels that the real beginning is Spring. I hope you join me in this journey and that your work in the journey blesses you, your human community and the more than human world.